By Agroempresario.com

The cultivated meat industry, once the darling of venture capitalists and sustainability advocates alike, is now navigating a precarious financial landscape. A new report from The Good Food Institute (GFI) underscores both the sector’s impressive technological progress and its increasingly dire funding challenges. According to the think tank, private funding alone will be insufficient to bridge the substantial financial gaps required to build and scale first-of-their-kind cultivated meat facilities.

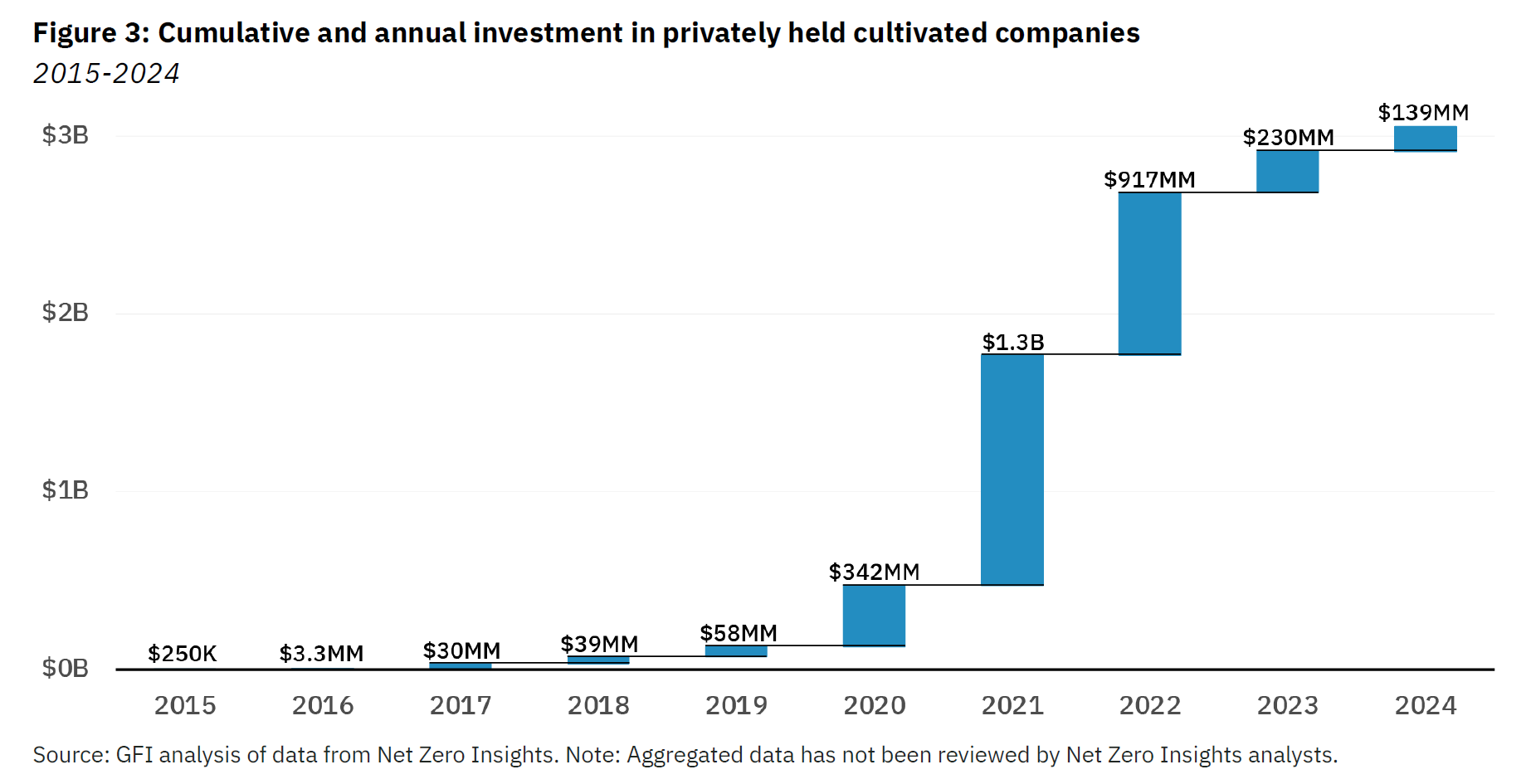

GFI’s analysis, developed in partnership with Net Zero Insights, paints a sobering picture. In 2024, cultivated meat and seafood companies collectively raised just $139 million — a figure that drops to $84 million if one excludes the $55 million investment in Prolific Machines, a startup that has since shifted its focus to therapeutics. This amount pales in comparison to previous years: $230 million in 2023, $917 million in 2022, and a record $1.3 billion in 2021. To date, little more than $3 billion has been invested in the sector over the past decade, a fraction of the venture capital funneled into electric vehicles in just the first three quarters of 2024.

Despite these funding woes, some companies still managed to attract substantial rounds. Leading the pack this year was Mosa Meat (Netherlands) with $43 million, followed by Ever After Foods (Israel, $10 million), Ark (USA, $8.2 million), and Simple Planet (South Korea, $6 million), among others. Yet, these amounts fall short of what is needed to build full-scale production facilities capable of making cultivated meat cost-competitive with conventional animal products.

The GFI’s report, Funding the Build, emphasizes that even if private investor sentiment rebounds, it is unlikely to reach the frenzied levels seen in 2021, when interest rates were low and alternative proteins were the trend of the moment. Venture capital, historically geared toward high-margin, high-growth tech ventures, is poorly suited to support the capital-intensive expansion required by cultivated meat companies.

“Venture capital is not typically well-suited to fund new facilities,” the report notes. “Companies looking to scale, especially via first-of-a-kind facilities, will likely need to identify alternative sources of funding.”

Among the alternative funding strategies proposed are equipment leasing, strategic partnerships with incumbent food and biotech players, support from sovereign wealth funds, blended finance models, and increased government support. Yet, GFI cautions, there is no "silver bullet" that can resolve the industry's funding challenges overnight.

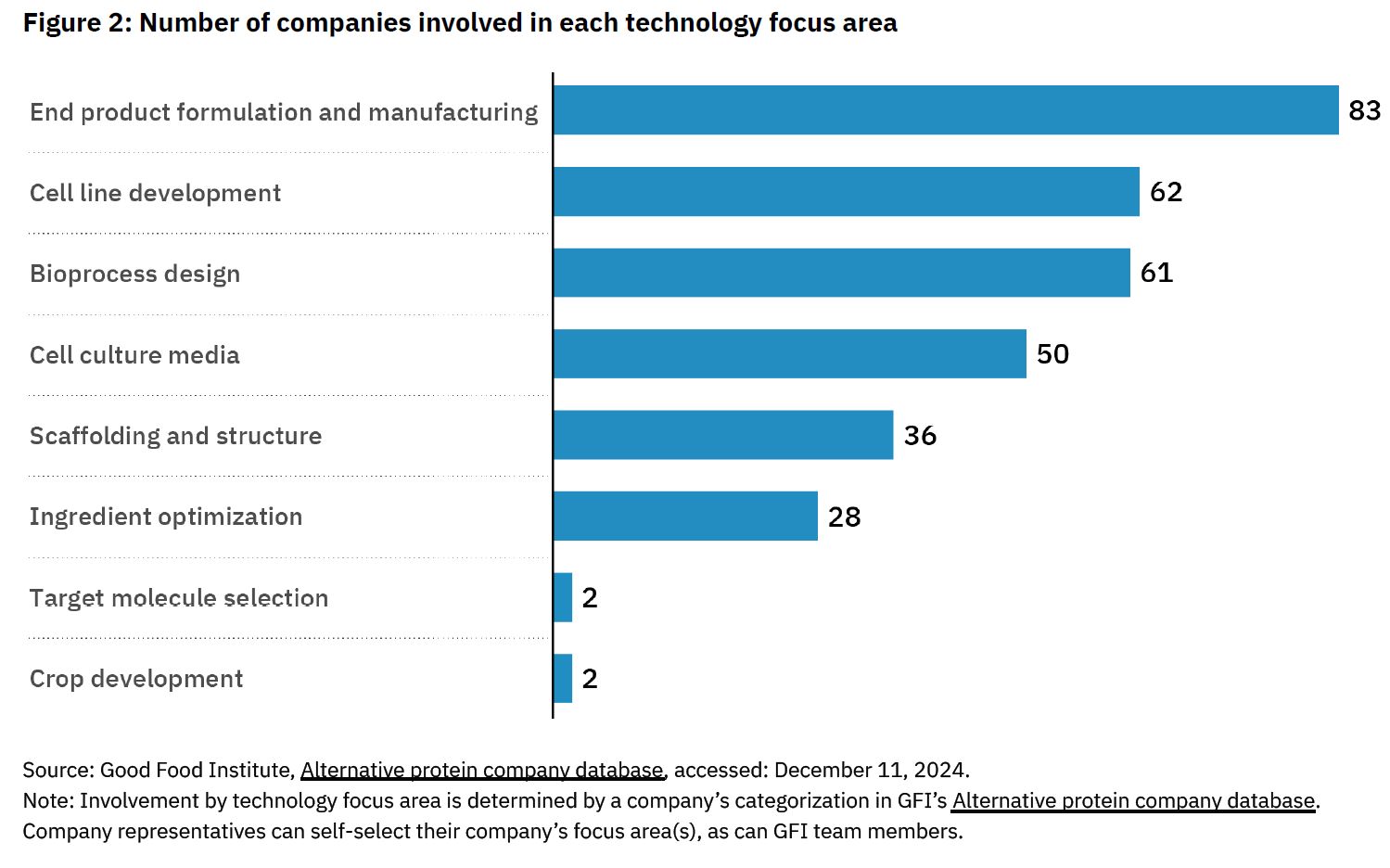

Without sufficient capital, many startups may have no choice but to downsize, consolidate, or close their operations entirely. The GFI database currently tracks 155 companies worldwide focused on developing cultivated meat and seafood products or supporting technologies.

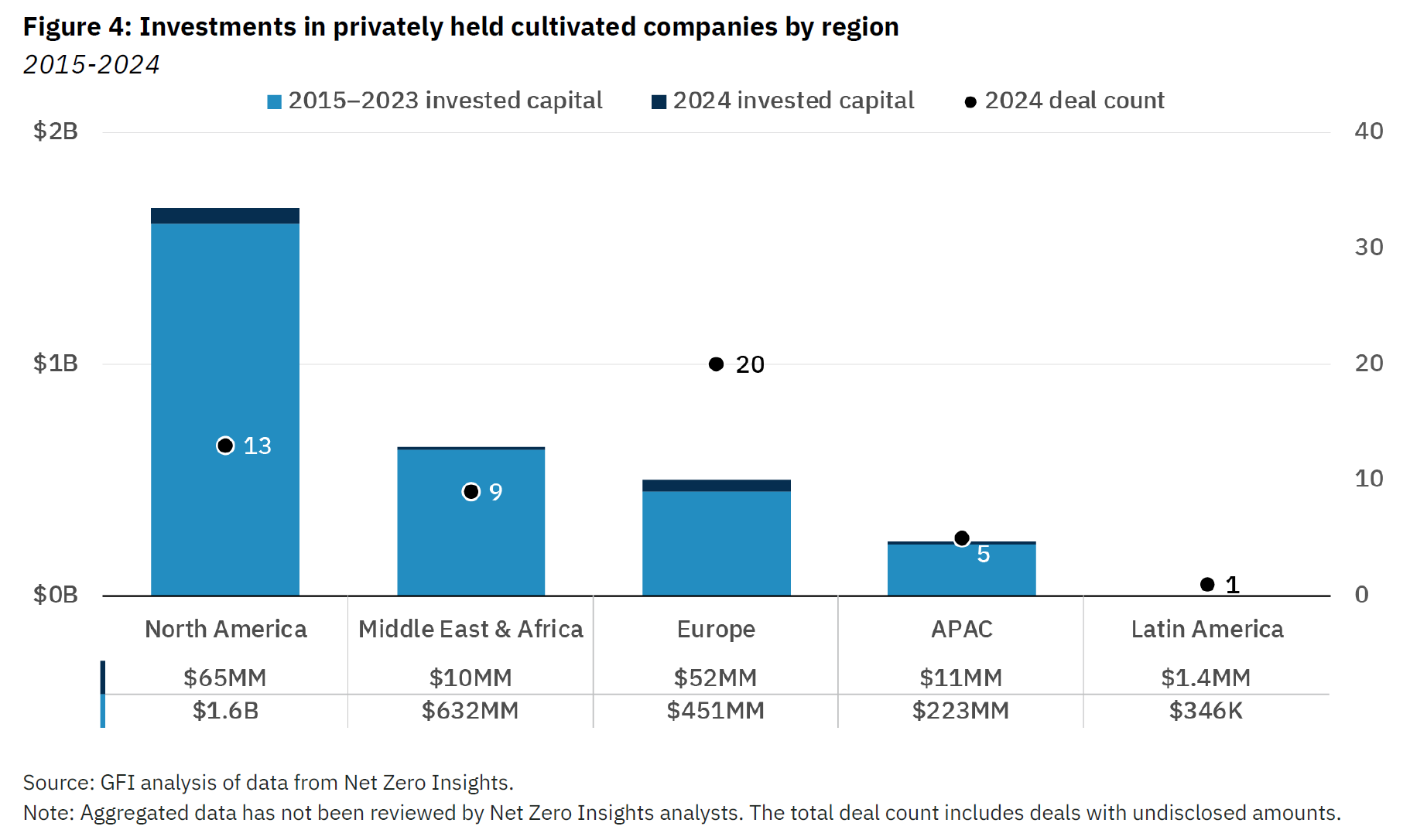

Fortunately, public funding is starting to play a more prominent role. Although some governments (such as Italy, Hungary, and certain U.S. states) have taken steps to restrict cultivated meat, many others are investing in it. China and India have made significant investments to bolster their domestic biotechnology sectors, including cultivated meat initiatives. Similarly, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and South Korea have launched public-private programs to fund research and innovation.

In Europe, the EU’s FEASTS project is evaluating the role of cultivated meat in future food systems. The UK’s National Alternative Protein Innovation Centre received £16 million ($21.4 million) in public funds to support research, while smaller grants were awarded by governments in Poland, the Czech Republic, Israel, and Brazil.

Massachusetts also authorized $10 million to fund research and infrastructure for alternative proteins, a promising sign that regional governments see potential in this nascent industry.

Still, as the GFI points out, government funding alone will not be enough unless paired with tangible progress in cost reductions, scale-up efficiency, and regulatory clarity.

The cultivated meat sector made important technical advances in 2024. Notably, several companies introduced new bioreactors and animal-free cell culture media that dramatically lowered production costs. A peer-reviewed study from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Believer Meats, for instance, showed media costs have fallen by over 99%, from pharmaceutical-grade baselines to $0.63 per liter.

Other breakthroughs include continuous manufacturing processes and reusable filtration technologies that further reduce operational costs. These innovations bring the industry closer to economic viability at commercial scales.

However, revenue generation remains a major bottleneck. According to the GFI, the cultivated meat industry remains "almost entirely pre-revenue," with only a handful of products available for purchase in Singapore, Hong Kong, and select locations in the U.S. The number of consumers who have ever bought cultivated meat remains in the mere thousands, while billions regularly consume conventional meat.

Moreover, several highly anticipated facility launches have been delayed or downsized. GOOD Meat, the first company to commercialize cultivated meat, has yet to find a profitable production model. UPSIDE Foods paused plans to build a large-scale facility in Glenview, Illinois, choosing instead to expand its smaller EPIC site in Emeryville, California. Similarly, Believer Meats' flagship plant in North Carolina, once touted as the largest in the world, remains under construction pending regulatory approvals.

Despite the setbacks, some positives emerged in 2024. Four new production facilities came online, including Multus’ serum-free media plant in the UK, Nutreco’s cell feed factory in the Netherlands, BLUU Seafood’s pilot plant in Germany, and The Cultured Hub in Switzerland — a contract biomanufacturing facility developed by Givaudan, Bühler, and Migros.

Meanwhile, companies like Mission Barns and Ever After Foods unveiled new bioreactor designs aimed at cutting capital and operating expenses. Mission Barns also achieved an FDA “no questions” letter confirming the safety of its cultivated pork fat, an important regulatory milestone.

Startups are also forging strategic partnerships. Dutch company Meatable partnered with Singapore’s TruMeat to establish a production site, while Australian startup Vow announced it is nearing unit-margin positivity with its new 20,000-liter bioreactor and expects to sell cultivated Japanese quail products in Australia and New Zealand following preliminary regulatory approval.

Israeli innovator Aleph Farms secured approval to sell its products domestically and revealed technology enhancements that will lower costs for producing whole cuts of cultivated beef.

Stepping back, the cultivated meat sector is a study in contrasts. Technological progress is accelerating, and regulatory frameworks are slowly taking shape in markets like the U.S., Singapore, Israel, Australia, and New Zealand. Yet the industry's commercial future remains uncertain.

Without more robust financing solutions — combining private, public, and hybrid models — many cultivated meat ventures may never reach scale. And for now, conventional meat retains a near-monopoly on the global plate.

Still, GFI remains cautiously optimistic: “The remarkable cost reductions in cell culture media, bioreactor innovations, and early regulatory approvals are important signals. If a handful of companies can demonstrate profitability and scalability, the private capital tide could shift once again.”

Until then, the industry will have to navigate a tough and uncertain journey, relying on a mix of creativity, patience, and strategic partnerships to survive and thrive