Monitoring livestock across thousands—or even millions—of acres has long been one of the most labor-intensive and costly challenges in animal production. In 2026, an Australian agtech startup is reshaping that task from the air. Drone-Hand, founded by Edward Barraclough, is deploying AI-powered autonomous drones to help livestock producers reduce labor hours, lower operational costs and detect animal health issues earlier, according to AgFunderNews.

Launched in 2023 and headquartered in Australia, Drone-Hand combines aerial robotics with machine learning to replicate routine livestock checks traditionally carried out on the ground or by helicopter. The system is designed to function offline, a critical feature for remote agricultural regions with little or no mobile connectivity. The company is already testing and commercializing its technology across Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada, with additional trials planned in Indonesia and South America.

Barraclough, who grew up on a mixed livestock farm in New South Wales, came to agtech from an unconventional background. He spent years working as an aerial photographer before recognizing the potential of drones beyond imaging. The turning point came when his father, then in his eighties, suggested that a drone capable of checking livestock could allow him to remain active on the farm longer.

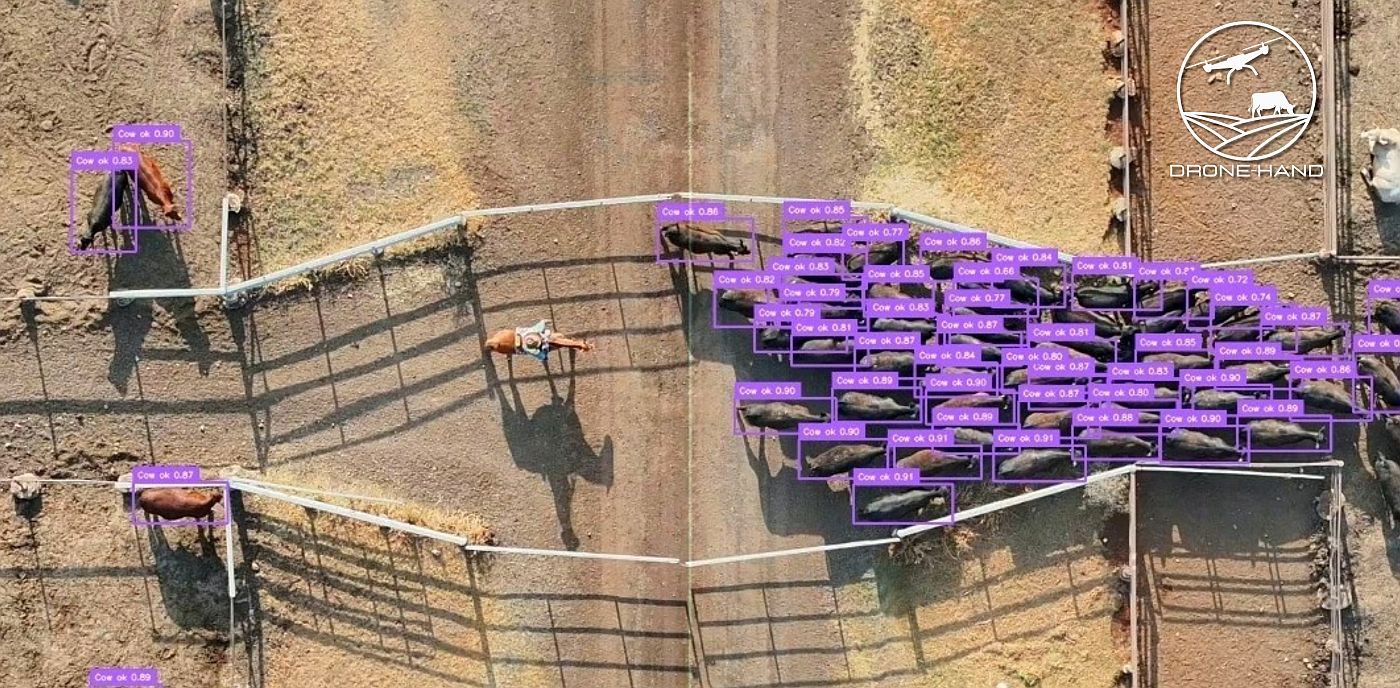

At the time, only a handful of companies globally were experimenting with drones for livestock management. Barraclough began exploring how computer vision and machine learning could be used to automate the daily decisions farmers make: counting animals, identifying injuries, checking water availability, monitoring fencing and assessing pasture conditions.

One of the first technical hurdles was connectivity. Much of Australia’s farmland lacks reliable internet access, making cloud-based analytics impractical. Drone-Hand addressed this by developing systems that process data in real time and entirely offline, allowing farmers to act immediately if an animal is in distress.

To build the technology, Barraclough partnered with Dr. Sebastian Haan, an AI and machine learning engineer. Together, they focused on two primary objectives: reducing the time spent on repetitive tasks such as stock checks and infrastructure inspections, and lowering preventable livestock mortality, a persistent issue that costs the Australian sheep industry millions of dollars annually.

By its second year, Drone-Hand had expanded beyond small and mid-sized farms using quadcopter drones. In northern Australia, where properties can exceed one million acres, the company introduced long-range fixed-wing drones capable of covering vast distances efficiently. These aircraft resemble small planes and are designed for extended flight times and autonomous operation.

The economic case is compelling. On large cattle stations, helicopter mustering can cost operators more than US$120,000 per year for limited periods of work. Drone-Hand’s systems operate at a fraction of that cost, offering continuous monitoring and, increasingly, autonomous mustering capabilities. The company is developing onboard reactive AI that responds dynamically to animal movement, adjusting pressure to guide herds toward trap points.

Interest from traditional service providers is growing. Two of Australia’s largest helicopter mustering companies have approached Drone-Hand to explore partnerships, acknowledging that drones are likely to augment—and potentially replace—some conventional operations in the future.

Beyond extensive grazing systems, Drone-Hand is also entering the feedlot sector. In collaboration with JBS Australia and Meat & Livestock Australia, the startup is testing fixed-camera computer vision systems that monitor animal condition, movement patterns and disease indicators in high-density environments. These deployments allow closer-range analysis than aerial systems and expand the company’s reach across different livestock production models.

By 2025, Drone-Hand had moved from pilot projects to paying customers in multiple countries. According to Barraclough, last year focused on trials, refinement and early adopters, while 2026 marks a shift toward scaling commercialization and generating consistent revenue.

The company operates a subscription-based software model, with hardware supplied through partnerships. For smaller farms, Drone-Hand resells commercially available drones bundled with its software. For larger, long-range systems, it collaborates directly with manufacturers. This year, the company plans to open an assembly and maintenance hub in Darwin, enabling local integration, leasing options and ongoing technical support.

Importantly, Drone-Hand’s platform is hardware-agnostic. While DJI drones remain common in Australia, the system is compatible with multiple manufacturers, including long-range platforms produced by an Indonesian company. This flexibility allows customers to use existing equipment or adopt new configurations as needed.

Competition in the livestock drone space remains limited but is growing. Early players focused primarily on data collection and post-flight analysis, often requiring reliable internet connections. Drone-Hand differentiates itself through real-time, offline decision-making. Other companies specialize in manual drone mustering or specific niches, but Barraclough notes that most players maintain collaborative relationships rather than direct rivalry.

Adoption, however, still requires overcoming skepticism. Barraclough emphasizes that successful pitches begin with farmers’ pain points rather than technology. “You can’t just come in and say I’ve got this magic tech that’s going to change your life. They’ve heard that before,” he said in comments reported by AgFunderNews. Demonstrating immediate return on investment is critical, particularly in labor savings and improved mustering efficiency.

From a technical perspective, detecting animal health issues from the air presents challenges. Drones typically operate around 100 meters above ground to avoid disturbing livestock. As a result, Drone-Hand has built extensive training datasets based on real-world farming experience rather than purely veterinary diagnostics. Visual and behavioral cues—such as isolation from the herd, abnormal posture or signs of flystrike—serve as early indicators that an animal may need attention.

In feedlots, where fixed cameras can operate at closer range, the system captures more detailed data. Still, Barraclough is careful to frame the technology as a decision-support tool rather than a diagnostic replacement.

Drone-Hand’s early development was largely self-funded through Barraclough’s previous photography business, supplemented by state and federal government grants. In 2025, the company raised a pre-seed round of approximately US$720,000, with half coming from agricultural industry investors and the remainder from Radius Capital.

While fundraising was challenging, Barraclough believes early traction helped validate the concept. At the time of the raise, Drone-Hand had more than 200 confirmed expressions of interest and active trials across multiple countries.

As labor shortages persist and operational efficiency becomes increasingly critical in livestock production, Drone-Hand is positioning itself at the intersection of automation, artificial intelligence and practical farm management. Its approach reflects a broader trend in agtech: solutions grounded in real-world constraints, designed not to replace farmers, but to extend their reach—sometimes by millions of acres.