Global agriculture is undergoing a structural repricing of risk and capital rather than a temporary downturn, according to an in-depth analysis published by AgFunderNews, which highlights how financial markets, corporations and investors are redefining their expectations for returns, innovation and resilience across the entire agrifood system. The shift is already visible in company valuations, investment flows and corporate strategies, and it is reshaping the balance of power from input suppliers to distributors, technology providers and data-driven platforms.

The central argument is that the market is no longer reacting only to short-term earnings cycles. Instead, it is reassessing the cost of capital, the durability of competitive advantages and the speed at which business models in agriculture lose relevance. Over the past decades, corporate lifespans have shortened across industries, and agriculture is no exception. The analysis stresses that, despite the essential nature of food, fiber and fuel, the sector’s traditional incentives and capital structures have tended to favor defense and incrementalism rather than long-term reinvention.

This repricing is visible first in the performance of major upstream players. Large input companies have faced sharp market corrections driven by a combination of factors: inventory adjustments in key markets, patent expirations, margin pressure, regulatory burdens and litigation exposure. Strategic decisions such as partial listings, portfolio separations or internal restructuring are interpreted as signals that legacy models of research and development no longer meet internal return thresholds when compared to alternative uses of capital. The growing influence of generic manufacturers and fast followers has also reset price ceilings in crop protection, strengthening retailer leverage and accelerating the expansion of private labels.

Downstream, the transformation is equally significant. Distributors are expanding their own brands and tightening control over shelf space, capturing more value through products they control rather than acting as pure intermediaries. Equipment manufacturers are repositioning themselves around precision agriculture, autonomy, software and data services, recognizing that hardware alone is no longer sufficient to sustain margins or valuation. Processors are navigating volatile margins, geopolitical disruptions in trade and increasing scrutiny around sustainability and traceability, which in turn raises the strategic importance of data infrastructure and verification systems.

The workforce dynamics reflect the same pressures. Since 2023, major companies in the sector have announced tens of thousands of job reductions. At the same time, experienced executives are leaving incumbents, more professionals are moving across industries and a growing number are founding or joining new ventures. The analysis suggests that this talent reshuffle is not a side effect but a core component of the structural shift underway.

Venture capital trends reinforce this interpretation. Global agrifoodtech investment has fallen sharply from its 2021 peak, forcing startups into more disciplined business models and accelerating consolidation. Fewer specialized funds are active, and capital is increasingly scarce. As a result, surviving companies are under pressure to demonstrate defensible intellectual property, credible regulatory pathways, strong unit economics and real distribution access. The environment favors fewer but stronger platforms over a fragmented landscape of early-stage experimentation.

Beneath these surface signals lies a deeper transformation driven by regulation, geopolitics, technological change and the economics of farming. Litigation risks, tighter regulatory frameworks and geopolitical tensions are colliding with rapid advances in artificial intelligence, biological inputs and digital tools. While AI is lowering the cost of early-stage discovery across chemistry, traits and biologicals, the gap between “promising” and “proven” solutions is widening because field validation, regulatory approval and farmer adoption do not accelerate at the same pace. This creates a new asymmetry: innovation at the front end becomes cheaper, but scaling and commercialization remain complex, slow and capital-intensive.

The analysis argues that agriculture is increasingly following a path similar to the pharmaceutical industry. Discovery is becoming more decentralized, while the greatest strategic advantage shifts toward late-stage development, regulatory expertise, manufacturing scale and market access. In this model, large companies may rely more on partnerships, licensing agreements and acquisitions of external innovation rather than on maintaining massive internal discovery engines. Competitive advantage moves from owning the largest laboratory to operating the most effective access-and-scale platform.

Despite these pressures, the article emphasizes that agriculture is far from broken. Demand for food is inelastic, and the sector continues to generate cash even under stress. What is breaking, rather, are the capital and operating models that defined the past half-century. The opportunity now lies in identifying where value compounds within the system. According to the analysis, these “choke points” include formulation and manufacturing capabilities, aggregated IP platforms, distribution networks, trusted advisory relationships, finance linked to inputs and offtake, and data layers that enable feedback loops across the value chain.

These positions benefit from recurring revenue structures and high switching costs, reinforced by regulatory complexity and channel control. Similar dynamics are already visible in adjacent sectors such as forestry and timber, where long biological cycles combined with data, asset control and financing create optionality around carbon markets, materials and land use. The implication is that agriculture’s next growth cycle will favor long-term orchestrators capable of aligning capital, science, regulation and go-to-market strategies into durable platforms.

Consolidation is described as both inevitable and, in many cases, necessary. Large incumbents face balance sheet constraints that limit their capacity for transformational mergers, pushing them instead toward structured partnerships and selective asset combinations. Startups face parallel pressures: overlapping technologies, fragmented commercialization strategies and limited funding are forcing difficult choices. The likely outcome is the emergence of fewer, larger platform companies that aggregate intellectual property, data, manufacturing and distribution through rollups and strategic combinations.

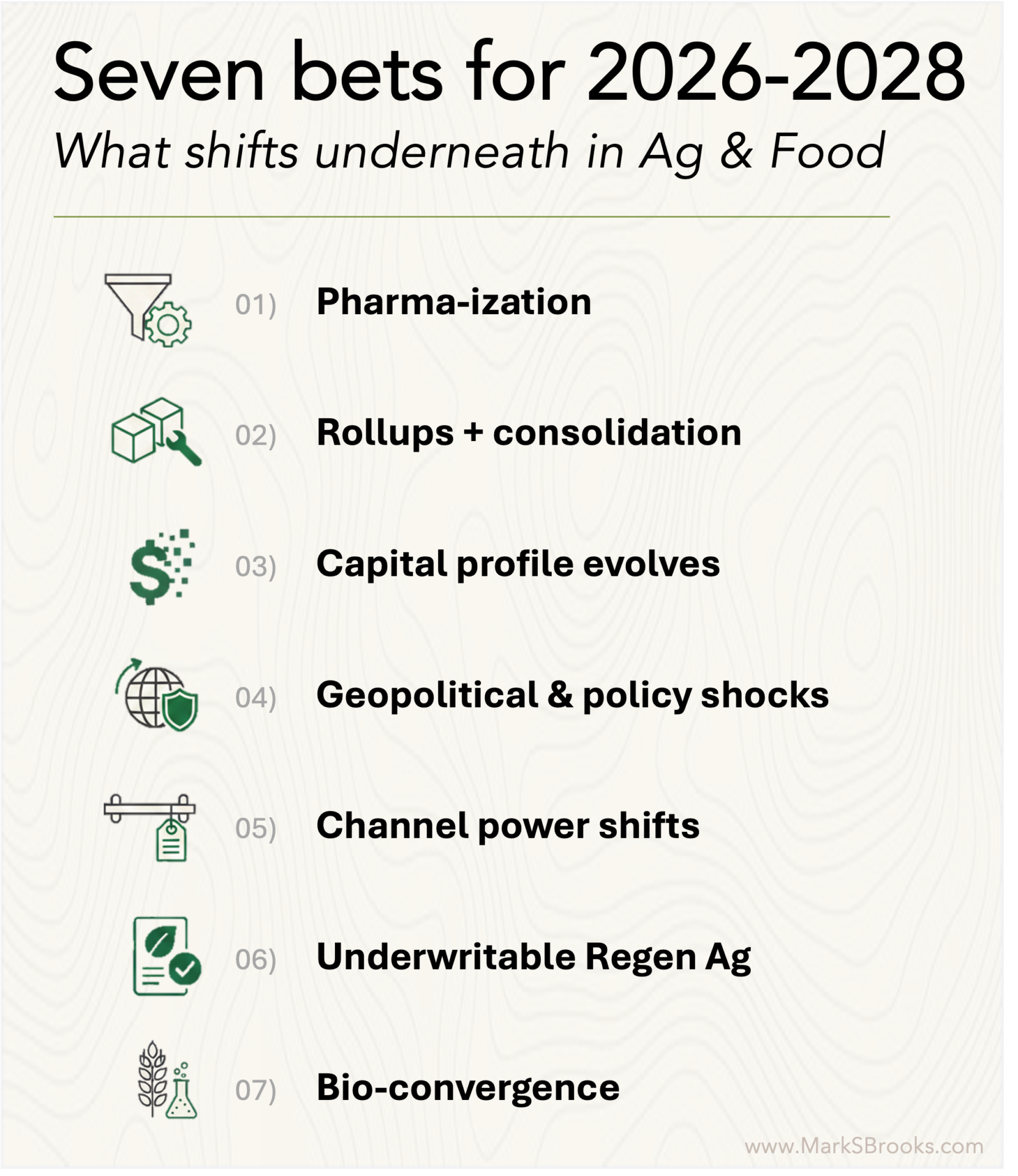

Looking ahead, the analysis outlines several trends expected to shape the period between 2026 and 2028. These include the continued “pharma-ization” of R&D spending, with flatter internal budgets and more external collaboration; multi-layer consolidation across assets and corporations; a shift toward more patient forms of capital such as family offices and blended finance; stronger influence of policy and geopolitics on corporate performance; growing power of distribution channels through private labels; the scaling of regenerative agriculture as outcomes become more measurable and financeable; and the integration of agriculture into broader value pools linked to health, energy transition and advanced materials.

The conclusion is clear: innovation in agriculture is not disappearing, but the old model built around scale for its own sake is losing relevance. The next cycle will belong to organizations capable of operating through volatility while maintaining a long-term horizon. In this environment, creating the future is no longer a risky bet compared to defending the past. It is increasingly the only viable strategy for sustainable value creation in global agriculture.